In October, two internal official communiqués on improving the 230-year-old Institute of Mental Health (IMH) in Chennai unexpectedly set the cat among the pigeons. In the first, Health Secretary Supriya Sahu wrote to Director of Medical Education and Research J. Sangumani, expressing disappointment with the lack of measures taken to improve the living conditions of IMH residents, and ordered the implementation of certain decisions already taken — modernisation of kitchen, budgetary allocation for food, attire and self-care kit, an MoU between IMH and an NGO, additional caretakers, and independent third-party evaluation of IMH.

In the second, she said there was a need for institutional reforms to make IMH a premier institution providing “gold standards” of care. The institute has huge opportunities to raise resources from national and international organisations as well as from Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) funds, and needs guidance from experts working in mental healthcare programmes, administrators, and people with extensive knowledge in the field of treatment, care, rehabilitation, and integration of recovered patients with their families and communities. “It is therefore essential that IMH is managed by a not-for-profit, wholly government-owned company registered under Section 8 of the Companies Act. This will ensure that the government company set up will have the financial and administrative flexibility and is able to get the required expertise from the board of the company.”

Over the days, however, this move came to be interpreted as the State abdicating its responsibility towards its patients, and professional doctors’ bodies expressed strong opposition.

Health Department officials insist that the current situation must be seen as an opportunity to clarify the role of the various actors in the mental health sector and move forward sufficiently fortified to serve those with mental illness in the best possible way — ensuring treatment, human rights, continuum of care, and psychosocial rehabilitation. But detractors allege that the proposal will make IMH a “company”.

‘State is responsible’

G.R. Ravindranath, general secretary, Doctors Association for Social Equality, said: “This stems from the National Mental Health Policy that encourages public-private partnerships, utilising services of civil society organisations and obtaining CSR funds. We are not opposing donations per se, but it is the State’s responsibility to identify the deficiencies and take measures to rectify them.”

The problem, however, will not be solved with a few donations, and in this instance, the government does not intend to give up control over the institution, as has been clarified several times since the controversy broke out. A senior official points out that the Tamil Nadu Medical Services Corporation Limited (TNMSC), which has a streamlined procedure for drug procurement, storage, and distribution, was incorporated under the Companies Act. It has since been able to bail out the State during shortages in the Centre-supplied drugs, and has won plaudits for its functioning. In fact, contesting the narrative that the State has abdicated its responsibility, the official says the proposal would increase accountability and transparency and bring in audits. In fact, the Special Purpose Vehicle envisaged in this case is a model that brings in flexibility and the opportunity to tap into funds. It helps in avoiding delays and action can be quick in providing care, and certainly it cannot be considered privatisation. Responding to questions from mediapersons recently, Health Minister Ma. Subramanian said the government would neither privatise IMH nor hand over its management to an NGO.

R. Sathianathan, former director of IMH, points out that for several years, funding was grossly inadequate and manpower was insufficient for IMH. He says the need of the hour is improvement to its infrastructure and renovation of its wards.

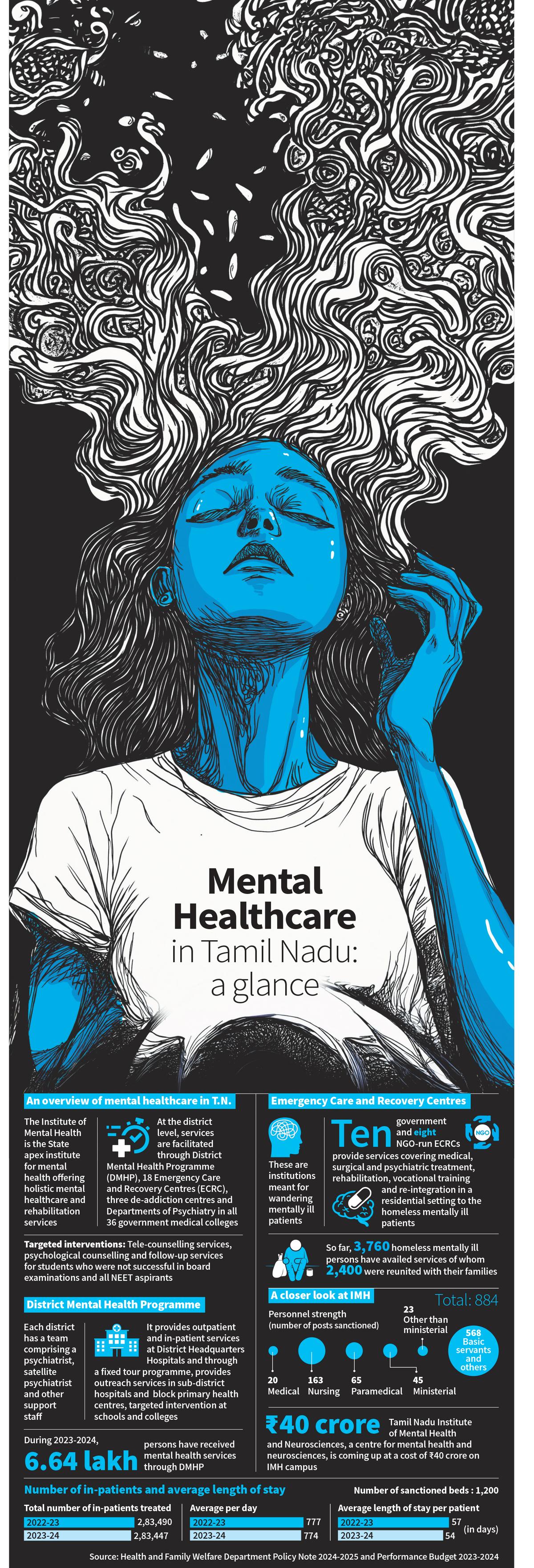

From a time when rescue and care of wandering mentally ill persons were difficult owing to tedious processes, the State has come a long way. It has simplified procedures to facilitate rescue and care of such persons, P. Poorna Chandrika, professor of psychiatry and former director of IMH, points out. “The establishment of Emergency Care and Recovery Centres (ECRCs) has reduced the number of homeless mentally ill persons to an extent in the State,” she adds.

At IMH itself, treatment and rehabilitation has helped a number of residents to be employed at various places; at least 20 to 30 persons have jobs now. Many IMH residents (who were rescued as wandering mentally ill) have been reunited with their families in India and abroad. IMH Director M. Malaiappan says that on an average, 5,000 patients are admitted and an equal number are discharged from the institute every year. “We have a system in place to trace and reunite patients with their families.”

Tamil Nadu has facilitated easy access to mental healthcare services in the districts through the District Mental Health Programme (DMHP). “Tamil Nadu offers extensive mental health services through DMHP clinics at government hospitals and block primary health centres (PHCs) across all districts. Over 600 government institutions offer psychiatry speciality outpatient department services under the mental health programme on a regular basis. The DMHP ensures sustainability, continuity, and comprehensive mental health services,” says R. Karthik Deivanayagam, Monitoring and Evaluation Officer for Mental Health Programme, Tamil Nadu.

The DMHP has facilitated accessibility: DMHP satellite clinics extend services to all government hospitals and block PHCs, and screening, referral, and follow-up services are available from the PHCs, and regular services (outreach clinics) are provided on the basis of a fixed tour programme to ensure fixed-day services at specific hospitals, he says. “The DMHP in Tamil Nadu has decentralised psychiatry services, bringing them within the reach of common man,” he adds. Essential psychiatry drugs and speciality psychotropic drugs, including clozapine, amisulpride, and olanzapine, are provided free of cost, enabling each family to save ₹2,500 to ₹3,000 a month.

NGOs that have been working in mental health for long also acknowledge the DMHP’s reach. Vandana Gopikumar, co-founder, The Banyan, says the DMHP has penetrated the under-serviced areas; people largely have access to psychiatrists and psychotropic drugs. However, the State should increase the number of psychiatrists on duty, she adds.

Lakshmi Vijayakumar, psychiatrist and founder, SNEHA suicide prevention centre, says Tamil Nadu is one of the best-performing States in the DMHP under which every district has a psychiatrist and a social worker. So, the rural poor have better access to mental healthcare services. In comparison with the other States, Tamil Nadu does have a psychiatry department at all government medical colleges. At most institutions, the department has a bed strength of 30, while smaller institutions have 10-20 beds.

Gaps in services

R. Thara, vice-chair, Schizophrenia Research Foundation, says mental health services are far better in Tamil Nadu than in other States, especially in north Indian States. “We have worked in States like Bihar where there are districts with no psychiatrists. Of course, there are still gaps in mental healthcare in Tamil Nadu; many people requiring care are not getting treatment. To improve access, the DMHP needs to train PHC doctors in treating persons with mental illness. Larger PHCs can be equipped with psychiatric medicines and training to reduce the gap,” she says. She pitches a separate cadre like Accredited Social Health Activists for mental healthcare for early detection and follow-up.

Employment opportunities for persons with mental health issues are still lacking and insurance does not pay for mental health treatment, Dr. Lakshmi Vijayakumar adds.

A government psychiatrist acknowledges the shortfalls: “Drug shortages occur now and then. Such shortfalls lead to relapse in patients.” He adds, “What we need are halfway homes and rehabilitation. The government should have a policy to enable persons with mental illnesses to participate in the workforce and corporate companies should step in to provide employment. We have to accept the fact that a certain percentage of persons have severe mental illnesses and are difficult to integrate. Such persons need long-term care.”

As far as the ECRCs are concerned, continuum of care remains a question. Another government doctor says, “Many are lost without follow-up. There is no mechanism to keep track of patients. In addition, there is no plan in place for social integration. Take this for instance: at least five to six patients continue to stay for nearly 1.5 years in one of the ECRCs.” Official sources underscore the need for additional funding and human resources for the DMHP at the block level, one counsellor per block, and an additional psychiatrist for the district headquarters hospital.

“When we started in the 1990s, mental healthcare was sporadic and fragmented, and awareness and access were minimal. We are an aware society now; however, prejudice and discrimination persist,” Ms. Gopikumar says. Robust integration of community inclusion into the care protocols will help, she says. “Convergence between the health and social sectors should be emphasised (with focus on disability allowance, housing, livelihoods) to address social determinants that impact mental health ranging from poverty, violence, devaluation, grief, or intergenerational distress. Social workers and psychologists should be better integrated into care systems to ensure adoption of value- and justice-based approaches. A cadre of mental health champions, who might be lived-experience experts or members of self-help groups and panchayats to form neighbourhood solidarity networks that aid crisis response and support continuity of care, is mandatory,” she adds.

Fostering collaboration

Tamil Nadu has done well to foster a sense of collaboration. The ECRCs are a case in point. They have improved access to appropriate care for ultra vulnerable groups, Ms. Gopikumar says, adding: “The task at hand is complex and large. To put the person with mental illness at the centre is key: the State is the primary stakeholder and accountable, and therefore should nurture impactful and engaged partnerships. We need to encourage and inspire a culture of collaboration and dialogue to ensure better outcomes, especially in an area fraught with inconsistencies and multifactorial causal pathways.”

Dr. Lakshmi Vijayakumar says the government has its own machinery, while NGOs have their ears tuned more to the ground. They are flexible, adaptable and respond faster to the needs of the community. “We need to find a seamless system wherein NGOs could be tasked to improve awareness and mental health literacy, identify and refer cases seamlessly to the health system that treats the person, and then the person is brought back to society for follow-up and rehabilitation. This will be a perfect scenario for a patient with mental illness,” she says.

Published – November 03, 2024 12:40 am IST

The post Putting patients at the centre appeared first on World Online.