This is an opinion column

Coretta Scott King wrote in 1970 that “almost anyone who can read or look at a television screen knows what happened in Selma that sunny, bloody afternoon.”

I don’t know if that was ever true. It’s not true now, 60 years to the day after men and women seeking the right to vote, to be seen as human in a state that balked at that, stepped on a bridge named for a Klansman and marched to a Bloody Sunday.

If America remembered, the country might be different now.

It’s easy to recall the moment atop the Edmund Pettus Bridge, when John Lewis and Hosea Williams led 600 peaceful marchers over the Alabama river.

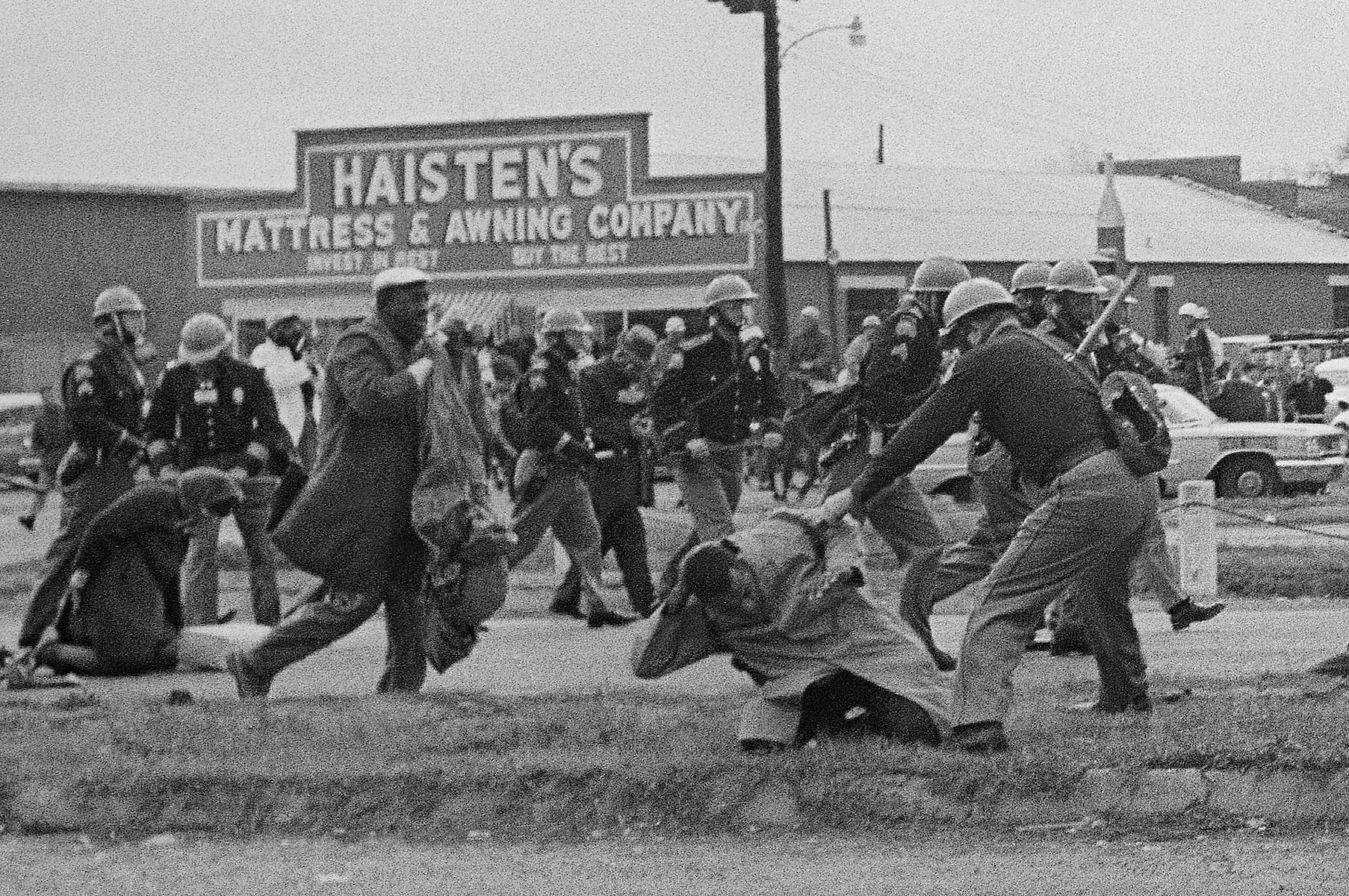

They crossed that bridge to face a phalanx of white state troopers. Major John Cloud told them to stop. He gave them two minutes to turn back. Before they could kneel to pray, Cloud ordered “Troopers, forward.”

The world saw that. Alabama lawmen, strongarms of the state, swung batons. Lewis fell, his head cracked open by a club. Others collapsed, crying from tear gas, as men on horseback charged with whips as if in battle. Like overseers on a plantation.

“The whole nation was sickened by the pictures of that wild melee,” Mrs. King wrote.

I know that’s not true. I’ve seen the picture that ran in Alabama’s Huntsville Times the next day, with the almost gleeful caption: “Negro marchers are put to rout.”

Which is why Selma is so much more than a beating. Especially today.

Try to put yourself in the black-and-white world of Alabama in the ‘60s. It’s a place where black people are allowed to vote only on the whims of white bureaucrats who give arcane poll tests (“The Constitution limits the size of the District of Columbia to what?”) to rob them of their voice.

Cities close pools rather than integrate them, white mobs spit on kids as they try to enroll in schools. Preachers are beaten, churches bombed, little girls killed.

Martin Luther King Jr. was noticeably missing from the Bloody Sunday march. He’d wanted it to happen another day. But he had worked to put Selma’s racial obstinance to the test. He knew, as he said two months earlier, that Alabama’s reaction could “touch the nation’s conscience.”

Those words, captured in an AP story by Rex Thomas, appeared all over the country, with very different headlines.

The Grand Rapids Press: “King sees massive test to end violence.”

The Staten Island Advance: “Dr. King hails new round of bias tests.”

Or the Huntsville Times in Alabama, under this sinister headline:

“Selma awaits Negro assault.”

The same was true the day after Bloody Sunday. On March 8, 1965, 60 years ago tomorrow the Ann Arbor News wrote: “Mauled Negroes seek court aid.”

The Newark Star Ledger: “Tear gas and clubs crush Selma march.”

And Alabama’s Huntsville Times: “Inevitable Selma violence was not long in arriving.”

Inevitable violence.

Selma, and the killings of Jimmie Lee Jackson and Viola Liuzzo and James Reeb, did touch a nation’s conscience. The Voting Rights Act became law five months later, giving assurance that skin color is not the key to citizenship.

What is often lost in Selma was what Lewis and King both knew. People of color would never find equality under Gov. George Wallace or his troopers. Black people in Selma would never fulfill a promise of freedom under cattle-prod-wielding Sheriff Jim Clark.

They had to get the attention of America, and its government, to assure freedom in places like Alabama that were eager to deny it.

“Next time,” Lewis said after he stumbled bleeding off that bridge, “we may have to keep going when we get to Montgomery. We may have to go to Washington.”

In 1965, at a time Alabama politicians preyed on fear, when crimes against black people went unsolved, when voting was a right for only some, the U.S. courts and the government were the hope for freedom.

That’s the story of Selma.

That’s the story of America today, too, a country marching across a bridge. In need of courage and determination and grit. For the first time in 60 years, the government is not coming to help.

John Archibald is a two-time Pulitzer winner.

The post John Archibald: This is not your grandmama’s Selma appeared first on World Online.